Georgiana Goddard King loved to chat. She begins Volume III of The Way of Saint James by retelling a conversation she had with an unidentified Spanish noble who hops on the train she is taking to Santiago de Compostela. Remarkably, she converses with him in French, not Spanish or English, and she seems genuinely surprised when he tells her he is forgoing the first-class carriage to ride in what she calls the “dim, close, dingy” third-class cabin. Everyone is going to the July 25 Feast of the Apostle, the noble is on pilgrimage, and this was his personal form of penance.

Once in town, she gets a room at the last minute at her favorite hotel because she knows the head waiter. She talks about having met the Archbishop briefly, and she speaks with a local man near the Cathedral who confesses to her that he’s never seen a bullfight. If she were in Spain today, my guess is that she would have business cards in her wallet from every taxi driver in town. Her conversations with strangers, priests, men in particular, inform her point of view: that the locals clearly can offer her a wealth of information about the places she visits and local customs. In The Way of Saint James, she freely fleshes out her discussions of medieval sculpture or the impact of foreign craftsmen on medieval Spanish church building with a little story about Boy Scouts going to Mass.

The men in King’s life fall into several categories. The men she knew personally, like Bernard Berenson (1865-1959), Leo Stein (1872-1947), or Archer Milton Huntington (1870-1955), all give her something she wants: typically, a privileged entry into their own circle of friends in Florence, Paris, and New York. Talking with Berenson at his Italian villa likely was essential to her early work teaching art history at Bryn Mawr when, with a background in Political Science and English, and after teaching at a girls’ finishing school in Manhattan, she suddenly started teaching Renaissance Painting in what was then called the Bryn Mawr Department of Archaeology.

Berenson’s wife, Mary Whitall Smith Berenson (1864-1945), was a cousin to M. Carey Thomas (1857-1935), then president of Bryn Mawr, and King met with both Berensons in Florence over many years. In all probability, it was Mary who gave her close friend, American writer Edith Wharton (1862-1937), a copy of The Way, or recommended it to her, for Wharton’s own journey along the Camino de Santiago in 1925.

Leo Stein, Gertrude Stein’s brother, brought King into the whirlwind world of modern painting in Paris in the years just before WWI. A Bryn Mawr student reporter in 1934 mentions in The College News the Steins’ influence on King’s learning to “understand it (modern painting) a little, with the aid of an introduction to Picasso’s dealer.” Visiting Leo’s gallery, meeting the painters, being a part of this dramatic turning point both in travel and in art – King was in her element, conversing with the taste makers in Leo’s small gallery and in Gertrude’s weekly salons. And she could learn from the artists themselves how they went about creating their work – all the better for this newly-minted Bryn Mawr Professor of Art History.

Archer Milton Huntington, the founder of The Hispanic Society of America in New York, published The Way of Saint James. There is no greater affirmation to a working scholar like King than to have someone with nearly limitless funding and influence take her seriously and support her need to travel. Huntington’s own fascination with Spain’s local costume and small villages surely encouraged her, on some level, to include so many little stories about the people she met while researching The Way in order to place her churches in some context. Her anecdotes about the sound of the bells or the way a church smells when she walks in are, in so many ways, the lifeblood of The Way.

But as supportive as these three men were to King, it was the two men she chose to travel with to Spain that gave her both a solid framework for her research and a clear, concise map for her to pursue it. Her constant spiritual, if not physical, traveling companions were Mr. George Edmund Street (1824-1881) and Sr. Vicente Lampérez y Romea (1861-1923). She kept them both symbolically, and inspirationally, very close.

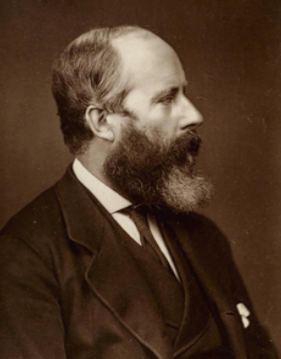

George Edmund Street, a British church architect and ardent ecclesiologist, died when King was still a child. His book, Some Account of Gothic Architecture in Spain (1865) was published at a highly significant moment in church building. With practicing architects struggling to preserve decaying structures and facing the need to build new ones, a certain framework for appropriateness in church building came about in the mid-19th century in England with Street at the heart of it. How wide, how long, how tall should a proper church be? Should there be pews (also called pues) or not? How is the altar area defined, what about stained glass, how many aisles is proper, transept or no transept? All of these questions had the same answer: Gothic. It was accepted broadly that the standard for constructing God’s houses was to be found in Gothic. Ironically, in an Anglican environment, the way to establish godliness fell to imitating13th century Catholic cathedrals: the theory being that Gothic churches inspired religious behavior and ritual by their very design. In many ways, it is so taken for granted now in the 21st century, that when you see a pointed arched Gothic window, in the absence of signs or crosses, you know right away that the building is a church.

Street wrote the book that laid out how King would approach collecting churches: know them all, categorize them by similar features, and then list them the way you might now casually list all the James Bond movies to compare plotlines or villains. It was likely the facility with which he discussed medieval churches that made his book so appealing to King. If it were King’s three volumes of The Way that guided Edith Wharton through Northern Spain to the Cathedral in Santiago de Compostela, it was definitely Street’s Some Account that guided King along The Way. While writing The Way, she republished his book in 1914 with her own pointed commentary on each chapter. Her notes are specifically addressed to Street’s observations and conclusions: where he simply must have misspoken, or where some facet of a particular church isn’t any longer the way he described. She reviews his hotels, mentions how modern rail travel has made all the difference in ease of getting around, and introduces further discussion of Street’s text by comparing it to what “Sr. Lampérez” has to say.

Vicente Lampérez y Romea, a still-living (while King was writing), Madrid-based architect, was in fact a colleague at the Hispanic Society of America. While the Hispanic Society published 16 titles in their Peninsular Series for King, they published a full 24 for Lampérez. King has a running conversation with him, not only throughout The Way, but also in her edition of Street’s Some Account. It’s as if Lampérez were reading King’s work alongside her – nodding in agreement, or shaking his head, that he would not be of the same opinion.

Like Street, Lampérez too wrote about medieval churches in Spain: a two-volume Historia de la Arquitectura Cristiana Española en la Edad Media, published in Madrid. Lampérez refers to Street’s work throughout the introduction to his Volume I in order to establish how he, Lampérez, developed the outline for the study of the churches and where his thoughts and Street’s coincided (frequently) or diverged (much less frequently).

“Sr. Lampérez” is introduced to us, along with “Mr. Street,” in the second paragraph of the Forward to The Way without any other reference to who they are or why she is chatting with us, as readers, about them. And her Pre-Romanesque Churches in Spain (Bryn Mawr, 1924), published just a year after Lampérez’ death in 1923, is dedicated to them both: A Los Nombres Inolvidables de George Edmund Street y Vicente Lampérez y Romea Homenaje.

Lampérez’ name comes up so frequently in The Way that it is easy to gloss over the reference and read on, but his impact on her way of thinking about church architecture is key to the way she addresses the various elements of each building. Once again, like with Street, it is his facile, conversational, casual tone in describing each church that must have impressed her. It comes across not as academic or unapproachable, but as storytelling, or as an interlocutor: this building we are viewing has a story to tell us, and this is what I hear when I stand in front of it.

It wasn’t enough to write about the “Christian Architecture” of medieval Spain, Lampérez was also intimately involved in the physical renovation of the cathedrals of León, Burgos, and Cuenca. He was an admirer of Eugène Viollet-le-Duc (1814-1879), Street’s contemporary, who was responsible for the large-scale, mid-19th century restoration of the Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris (see note). Effectively, the approach of both architects, Lampérez and Viollet-le-Duc was to “Gothicize” the building, based on their interpretation of the proper way a cathedral should look. Gothic simply meant church.

How did these two passionate men, Mr. Street and Sr. Lampérez, impact The Way? In some respects, they gave King context and the freedom to pepper her discussions of the foreign influence on various tympana and capitals with long passages that detailed local Spanish history. They both chatted with their readers, freely referring to their colleagues, to what might have been a common understanding, or misunderstanding, of a particular structure, to literature, or to passages from poets or the Bible, creating a feeling in the reader that they were now fellow cognoscenti. And then, so did she.

They gave King an outline that was exciting for her to follow. Once she started down the path, discovering one fascinating church after another, she could lay out the route along the Camino Francés and discuss one location after the other, with a friendly nod to both Lampérez and Street interspersed with the poetry of the jongleurs. She argues in the Foreward to Volume I of The Way that she does not want to supplant their work, because “At León, (for instance) Sr. Lampérez had already made such a study. The intention being to supplement his work and Street’s great book, not to compete with them …”

With her supplement, we learn so much about the Spanish people, their dress, the modes of travel, the conditions of the road, the tiny villages, Spanish history, Saint James, and the effect of the political climate on an American in Spain, not that many years after the Spanish-American War (1898). King got around by chatting up anyone who would speak with her. She stopped, she observed, she made friends, and she took notes. The Way is the remarkable book that it is because of her extraordinary curiosity and her many friends – especially the dearly departed “Mr. Street” and her colleague, “Sr. Lampérez.” As working architects themselves, they could offer her something that Messrs. Berenson in Florence, Stein in Paris, and Huntington in New York could not – they showed King how to look at an old building and actually see it.

And, as she says, “every beginning has its antecedents.”

—————

– Some Account of Gothic Architecture in Spain, George Edmund Street, London, 1865:

https://archive.org/details/someaccountofgot00stre_0

– Edited by King, London, 1914:

https://archive.org/details/someaccountgoth00kinggoog/page/n2/mode/2up

– Memoir of George Edmund Street, R.A., 1824-1881, Arthur Edmund Street (his son), London, 1888:

https://archive.org/details/memoirofgeorgeed00stre/page/n9/mode/2up?q=Leon

– The Ecclesiologist newsletter (Volume XII, 1841):

https://archive.org/details/ecclesiologist43socigoog/page/n8/mode/2up?q=George+Edmund+Street

– Historia de la arquitectura cristiana española en la Edad Media según el estudio de los elementos y los monumentos, Vicente Lampérez y Romea, Madrid, 1908:

Volume I: https://archive.org/details/HistoriaDeLaArquitecturaCristianaEspaolaEnLaEdadMediaSegnEl

Volume II: https://archive.org/details/HistoriaDeLaArquitecturaCristianaEspaolaEnLaEdadMediaSegnEl_938

– Lampérez short biography: https://dbe.rah.es/biografias/11593/vicente-lamperez-y-romea

Note: It is said that three sacred relics were inserted into the new spire at Notre-Dame de Paris when it was placed on the roof of the cathedral in 1860, much like the way the medieval clergy would have placed their jeweled rings into the cornerstone of a new church. One relic, a thorn from the Crown of Thorns, was placed in the spire by Viollet-le-Duc himself.

According to https://www.friendsofnotredamedeparis.org/cathedral/artifacts/spire/ the wood in Viollet-le-Duc’s spire alone weighed 500 tons. Additionally, to keep the wood structure from the elements, it was encased in lead. His spire has recently been replaced, after the devastating fire of April 2019 sent the 19th century spire crashing through the roof of the cathedral. (Photo credit, Notre-Dame de Paris: the author, November 2018).

ANNE BORN (Firma invitada) / Escritora, peregrina, fotógrafa…