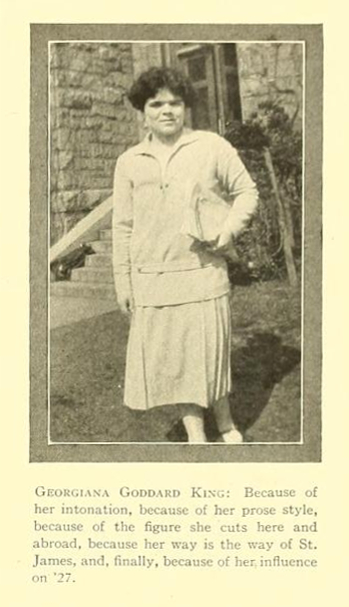

Georgiana Goddard King[i] ran with a pretty fast crowd. Never content simply to admire a work of art without examining thoroughly its artistic, literary, poetical, geographical, and historical context, King surrounded herself with the people she could mine for their scholarship and their friendship. Her wealthy friends were also abundantly rich in their passion for art, for literature, for history, for travel, and for each other. They discussed – endlessly – and they wrote both fiction and nonfiction about each other: what they’d seen, who they’d met, what they bought, and where they’d been.

Specifically, during the years King was researching and writing The Way of Saint James,[ii] a number of her friends stand out. This list is hardly exhaustive, but if Aesop is correct, that you are known by the company you keep, this might shine some light on who was with her while she was writing.

Every day spent teaching at Bryn Mawr College, Georgiana Goddard King was surrounded by frothy undergraduate ladies. In many cases, they had been sent there solely to become more interesting to prospective rich husbands and to construct tight knit circles of likeminded, bored, yet entitled women. In the years that King spent traveling, photographing, and writing in Spain (roughly 1910-1917), her students were in their rooms, worrying about the correct seating at garden parties, and ridiculing their instructors. Gertrude Stein would describe this as “the gently bred existence of my class and kind.”[iii] The Bryn Mawr The College News gave a three-word evaluation of King’s book:[iv] “Her studies have dealt in the most part with monuments, especially the… Romanesque ones, which she has recently written about in a curious work, a book about the Way of Saint James.”

But all the while, something extraordinary was happening. Their art teacher was opening a door – aided by the company she kept.

Edith Hunn Lowber[v] was, along with the patronage of the Hispanic Society of New York, the key to King’s success in Spain. She was King’s trusted photographer, traveling companion, and a dear friend. It is not clear how they met or how exactly she was entrusted with providing the photos in The Way of Saint James, but their collaboration begins around 1904, according to a passport application where King established how long she’d known Edith. While King was perfectly capable of working abroad by herself, she did not enjoy it, and she wrote about the challenges women faced when traveling alone. Edith’s presence must have had a stabilizing effect on King, making the long days they spent traveling and writing together much more pleasant than the lonely time King describes when she traveled alone.

Edith goes on to work on several more projects with King: including Pre-Romanesque Churches of Spain[vi] and Heart of Spain,[vii] possibly their most important collaboration.

Mary Douglas Newcomb[viii] was an 1896 Wellesley grad (B.S.), and both a photographer and a translator who met King sometime in 1906. Like Edith, her name comes up frequently in travel documents – both in ship manifests and passport applications. The three women, King, Edith, and Mary, sailed at least once to Europe together.[ix]

The following year, on February 22, 1917, King wrote individual letters in support of passport applications for both Edith and Mary, that they are going abroad together, ahead of King this trip, in order to save time. Mary apparently had “a greater knowledge of continental languages,” and she was expected to “arrange some matters (for King) with the Papal Nuncio”[x] who is acknowledged in the preface to The Way.[xi] Mary was going to Europe “to assist Miss Lowber and do work for me.” Why? Because, as King puts it, “It is unpleasant for a lady to go about alone in the South of Spain and it is necessary for Miss Lowber to go about my work.”

After Edith dies in March of 1934, Mary and King sail to Europe together that following fall. The loss of Edith on that trip must have been palpable. They seem to have been more of an indomitable trio than has been previously discussed and King calls Mary “my friend, Mary Newcomb,” in an account of that trip together.[xii]

According to the US census, in 1950, Mary still lived close to Bryn Mawr long after both Edith and King had died; her neighbors were mainly Bryn Mawr professors and students. She died in 1957. It is not clear what role she played at the college.

Martha Carey Thomas,[xiii] or as she preferred, Carey Thomas, was elected the second president of Bryn Mawr in 1894 – when King was still an undergraduate. Carey was a feminist, a suffragist, an avid anti-Semite and racist, and singularly connected, through her father’s family, to one of the most prominent art-affiliated men of the turn of the century, Bernard Berenson.

Carey had a two-decade-long relationship with Mary Mackall Gwinn[xiv] who left her in 1904 to marry a fellow Bryn Mawr faculty member, Alfred Leroy Hodder. Shortly thereafter, Carey began seeing Mary Elizabeth Garrett[xv] who, when Mary dies, leaves Carey to inherit what is estimated to have been a $15 million estate. Despite her Quaker upbringing, Carey is reported to have spent the money on lavish residences and outlandishly expensive travel. On a trip to India, she was reported to have brought three dozen trunks, and in her will, she leaves fine clothes and several pieces of Vuitton luggage to her family and her maid.

Carey traveled with King briefly on a trip that was reported in the Bryn Mawr The College News, June 1920, and separately without King, but with Edith. In Carey’s will, she leaves to her sister-in-law, Josephine Carey Thomas, “…my red smoking set (tray, cigarette box and matchbox and four copper ash trays) given me by my friend, Edith Lowber.” Edith died at Carey’s villa in France.

Additionally, Carey bequeathed “… to my friend, Georgina Goddard King, … all the books of prose and poetry written by herself which she has given me at various times …, the ancient Ecclesiastical seal made into a paper-weight which I used on my study table in the Deanery which she gave me on January 2nd, 1922[xvi] and the ancient Buddha priest’s breast ornament set with paste stones which I purchased for her in Egypt which was later mislaid and found only when the Deanery was handed over to the Deanery Committee in 1932; the ring made of an old seal bought in Carthage, belonging to the late Edith Lowber and worn by me since her death; my framed photograph of the said Edith Lowber, and some other articles that belonged to her that I will enumerate separately and append to my said Will.” Her personal correspondence with Mary Garrett was to be burned.

It was Carey’s approval of King’s multiple and sequential academic leaves that allowed King to travel extensively to Spain to complete the research for The Way. King traveled at a pivotal moment in her academic career, having founded the Art History Department while working on The Way book. Carey wrote a letter in support of King’s passport application on May 4, 1917.

A century later, in 2017, in response to student protests over Carey’s statements on how important it was to her that Jews and Blacks be denied admittance to Bryn Mawr, the college removed Carey’s name from two campus buildings. They are now called the Great Hall and the Old Library.

Mabel Foote Weeks[xvii] was an 1894 Radcliffe grad who had a three-decade-long career both as an English professor and academic administrator at Barnard College in New York. Mabel corresponded with Gertrude’s brother, Leo Stein, at some length over the course of many years, discussing his personal challenges, D.H. Lawrence, Picasso, Gertrude, psychology, and generally, his life in France and in Italy.

King reported to students at a Bryn Mawr lecture in 1934 that she met Gertrude “first in New York through Mabel Weeks, and Estelle Rumbold(t), the sculptor.”[xviii] Gertrude, Mabel, and Estelle lived, along with Harriet Clark, at “The White House,” on the corner of Riverside Drive and 100th Street.[xix] But how they all became acquainted in the first place depends on who you ask. In the Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, Gertrude met King first in Baltimore.

Estelle Josepha Isabella Rumbold Kohn:[xx] Who could possibly be a more valuable resource to a Romanesque sculpture and architecture historian like King than Estelle and her husband, Robert Kohn. Estelle was a prize-winning sculptor and Robert, a prominent civic architect in New York. Estelle studied with Augustus St-Gaudens at the Art Students League of New York.[xxi] Robert was the architect of Temple Emmanu-El and a colleague of Clarence Stein (not related to Gertrude) who worked in the earliest days to lay out the Appalachian Trail. Robert also worked with Bertram Goodhue, the architect of the Gothic Revival Rockefeller Chapel in Chicago.

Gertrude Stein[xxii] is easily the most generally well-known in King’s circle of friends. Gertrude and Alice B. Toklas met up with King in Madrid, while she was doing research at the Biblioteca Nacional,[xxiii] and she is credited with encouraging Gertrude to write. It was mostly the income from Gertrude’s writing that underwrote the cost of her artist salons.

On the afternoon of February 15, 1934, King gave a lecture at Bryn Mawr about Gertrude’s unconventional writing style.[xxiv] In this talk, King became both an apologist and interlocutor for Gertrude’s writing style, likening it to the modern paintings she collected. King remarked, “One cannot take the word as a unit, or the phrase, nor the sentence. There are no units. It is a whole long rhythm.” King is reported to have quoted “from nearly all of Gertrude Stein’s books” during that talk.

According to the account, “Stein liked to visit Miss King in her ‘penthouse’ apartment on 57th Street, cram herself out of the window to admire the vista of the river and the buildings, and finally settle down to talking at length about everything from art to psychology. … King did not see Miss Stein again until just before the War (WWI), when she enjoyed looking at new French painting and learned to understand it a little, with the aid of an introduction to Picasso’s dealer.”[xxv]

In November 1934, Gertrude gives a lecture – at Bryn Mawr – entitled “Poetry and Grammar,” where she talks at some length about nouns, verbs, and the uselessness of adjectives. Gertrude gave a string of similarly themed writing lectures in the United States: “Her lectures went off well. Her audiences, if addled and bewildered by her pronouncements, were also entertained by this roughly dressed woman, with close-cropped hair that set off her strong features.”[xxvi] Mary Newcomb and King would have just returned to Bryn Mawr from Genoa a few weeks earlier in September.

The door that Georgiana Goddard King opened by writing The Way of Saint James was, to put it simply, huge. She drew so much from her friends, and she taught a generation of art historians, both women and men, to step back and view the larger picture, not just the one hanging in front of them. She networked her way in and out of dozens of Spanish churches in one of the most exciting periods of artistic development and set an example for women scholars for generations to come: including Agnes Mongan, who was one of King’s Bryn Mawr students, as well as director of the Harvard Art Museum, and editor of The Heart of Spain.

King was influential both as a medieval art historian and as a seasoned traveler. The borders she crossed were more than the physical ones that travel guides like Baedeker would have described in those years around the First World War. In The Way, she merged art history with travel memoir in a uniquely personal fashion that must have charmed her readers but was ultimately dismissed by her mostly male colleagues in academia. She genuinely wanted Americans to travel to Spain, and American novelist Edith Wharton, for one, not only went to Spain but she carried King’s three-volume The Way book with her.

Imagining Georgiana Goddard King’s trajectory as an academic and art historian without the influence of these friends would be a fascinating study. She may have dropped The Way project for lack of someone to go with her to photograph (Edith). She may not have gotten all the help she needed from the Catholic Church (Mary) to open all those real doors. If she hadn’t met Gertrude Stein or Gertrude’s friends (Mabel and Estelle), she might not have crossed paths with any number of painters, sculptors, and architects who would have furthered her understanding of the artist’s method and the artist’s challenges.

Without Carey Thomas, she might have been subject to an administrator who was less than enthusiastic about her taking so much time away from her students or who didn’t value Spanish art as a topic. In short, her groundbreaking scholarship and vivid personal accounts might never have been published. But, thankfully, this was the company she kept. And, as Cole Porter would have said, “What a swell party it is.”

[i] b. August 4, 1871 West Columbia, West Virginia – d. May 4, 1939 Hollywood, California

[ii] Hispanic Society of America, 1920

[iii] The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas. Harcourt, Brace & Company, 1933

[iv] October 2, 1926

[v] b. June 6, 1879 Camden, Delaware – d. March 22, 1934 Beaulieu-sur-Mer, France

[vi] Bryn Mawr Notes and Monographs 7. New York: Longmans, Green, 1924

[vii] Ed. Agnes Mongan. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1941

[viii] b. May 20, 1870 Beloit, Wisconsin – d. October 1957 Bangor, Maine

[ix] May 27, 1916

[x] Francesco Cardinal Ragonesi S.T.D. J.U.D.

[xi] Volume I

[xii] The College Alumni Bulletin (1934)

[xiii] b. January 2, 1857 – d. December 2, 1935 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

[xiv] b. February 2, 1860 Baltimore, Maryland – d. November 11, 1940 Princeton, New Jersey

[xv] b. March 5, 1854 – d. April 3, 1915

[xvi] Carey’s birthday

[xvii] b. 1872 (?) – d. August 22, 1964 Nantucket, Maryland

[xviii] Bryn Mawr The College News, 1934-02-21, Vol. 20, No.14

[xix] Mentioned in The Flowers of Friendship, David Gallup, Octagon Books, 1979

[xx] b. 1873 St. Louis, Missouri – d. August 7, 1978

[xxi] According to Who Was Who 1564-1975: 400 years of artists in America

[xxii] February 3, 1874 Allegheny, Pennsylvania – July 27, 1946 Neuilly-sur-Seine, France

[xxiii] The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, and Bryn Mawr The College News

[xxiv] It was reported at length in Bryn Mawr The College News with a subtitle “Technique Is Oriental.”

[xxv] Most likely in this period before WWI, it was Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler

[xxvi] “Gertrude Stein Dies in France, 72.” New York Times, July 28, 1946

ANNE BORN (Firma invitada) / Escritora, peregrina, fotógrafa…